It’s time for me to bear witness

—–

I do not know why 2025 should be the year, 24 years after the fact, that I should write down my account of the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

Perhaps it’s the feeling that, having been so far away from the scene — geographically, personally, emotionally — and relatively safe with no-one I knew involved, that I felt my story did not have sufficient weight to justify its telling. Best to stand back and allow the families of the victims and those who witnessed the events first-hand the space and dignity to tell theirs.

I’m also unable to say why writing this account on the 24th anniversary seemed like the way to go rather than on a “rounder” anniversary like the 20th or the 25th. Perhaps it’s because stories tend to have a life of their own and gestate for as long as they want before saying “We’re ready now”.

Or it may have been my visit last year to the memorial at the Pentagon and realising that the children who died on Flight 77 that day would now be fully-grown adults, possibly with children of their own.

24 years is a very long time.

In any case, one of the reasons I started writing regularly three years ago was to tell the stories that I’ve collected in the 43 years I’ve been around. And — for those old enough to properly remember it, 9/11 is probably one of the most brilliantly illuminated stars in the night sky of one’s own memories.

A recollection all the more unusual because it does not truly belong to you. It is part of a larger, collective Western consciousness brutally knife-sliced through into a “before” and an “after” by the events of that sunny September morning.

Most people will be able to tell you exactly where they were, whom they were with and how they felt when they first learned about the attacks.

I was in London, finishing up summer break after my first year of my law and languages degree at University College London. Not having been able to stomach the thought of spending the summer stuck in the tiny, ultra-uneventful Yorkshire village I’d left a year ago, I’d stayed in the Big Smoke doing grubby cleaning and bar work in exchange for cheap accommodation and saving some money for the next year of study.

In the weeks before the start of autumn term, I was also spending some time at a barristers’ chambers in the City being the world’s worst intern. Acting the part of a conscientious law student barrelling towards the requisite glittering London legal career when I already knew full well that it wasn’t the thing for me (to find out how well that went, click here).

When the planes hit the twin towers, I must have been on the underground travelling from the law offices to the bar of the UCL Student Union where I worked in the evenings.

I do not remember anything unusual in the demeanour of the other passengers on the train, on the escalators or in the lifts: nothing that would suggest an awareness of what had just happened across the Atlantic.

There was no Twitter then, of course — no lightning-fast new coverage or messaging apps that would deliver first witness reports to your retinas within seconds. In 2001, we were allowed the luxury of not knowing for a little while longer.

I also didn’t notice anything strange when I got out of the Tube station at Russell Square. Just the same streams of perma-harassed Londoners hurrying onwards, trying to get from A to B.

The first time I noticed that something was “off” was when I walked towards the entrance of the ground floor bar and saw that it was packed — way too crowded for a Tuesday afternoon several weeks before the beginning of term. All the people in there seemed to be staring up at the tiny bar TV in the front corner of the room, looking drawn and glum.

I push my way through to the bar and greet my colleagues, jokingly asking which football teams are playing today to cause such a crowd?

My boss — usually quick to laugh and join in with the joke — stays serious.

“You know the twin towers in New York?” she asks in her Cockney accent, thick and twangy.

“Sure, I say — I went up them last year, the view from the top’s fantastic!”

“Well, they’re gone”, she says, wiping out my elan. “Planes flew into them. And into the Pentagon. Another plane crashed. Lots of people dead.”

I don’t recall whether she said anything about it being terrorism. It was about 5pm GMT — just a couple of hours after the planes hit and crashed — and we were still in the dark about the nature of the attacks and who might be behind them. A naiveté which now strikes me as rather quaint.

In just a few hours, I will hear the name Osama bin Laden and Al Qaida for the first time, followed some time later by “axis of evil”, “war on terror” and all of the other sorry vocabulary that would form the script of Western geopolitics for the next 20 years.

But right now, all I can do is squint disbelievingly up at that clapped-out bar TV. I see endless piles of rubble, lots of smoke and terrified people. So many terrified people, running helter-skelter through New York in their expensive suits and ties, mouths agape.

The presenter tells me this pile of grey dust is what has become of the World Trade Center — the same World Trade Center that I stood atop one year previously, staring uptown at Manhattan which looked like a computer-generated image in the hazy summer heat.

It is entirely incomprehensible to me. But I don’t have time to ruminate because I’m at work now, there are a lot of people at the bar settling in for the evening to watch the events unfold and they need serving. So I peel my eyes away from the TV and start pulling pints, steaming milk and warming up cheese toasties. Thankful perhaps that I can occupy myself with these banal tasks instead of having to meaningfully engage with the news.

The mood in the bar is subdued and surreal. But silence can also say a great deal and this one tells me that we all know that something truly epoch-defining has happened. But we’re going to have to generate a whole new sub-language to talk about it, so for now we’re all just carrying on doing the things we know how to. Ordering food and drinks, chatting to friends and putting glasses through the dishwasher — but feeling vaguely indecent in doing so when things are currently 100% the opposite of normal.

Two girls drift up to the bar. This being the student union of an elite UK university, it is choc-full of clever young people who think slightly too much of their own intellect and that no matter is complete unless they have made some pronunciation on it. In any case, one of these ladies gestures up to the TV and says loudly to the other in a way which is meant to be overheard:

“This will have ramifications”.

No shit, I think. What a spectacularly stupid thing to say. In the years since, I’ve come to look upon this unknown girl in a milder, more charitable way. Like the rest of us, she was just trying to get through this oddest of days when nothing was as it should be. But at that moment, I wanted to take the pint of Caffrey’s ale she’d just ordered and throw it right down her front. Perhaps a prize academic specimen, but a prize fool too.

By the time darkness falls, the crowds have dripped away, presumably going home to follow the rolling news coverage at home.

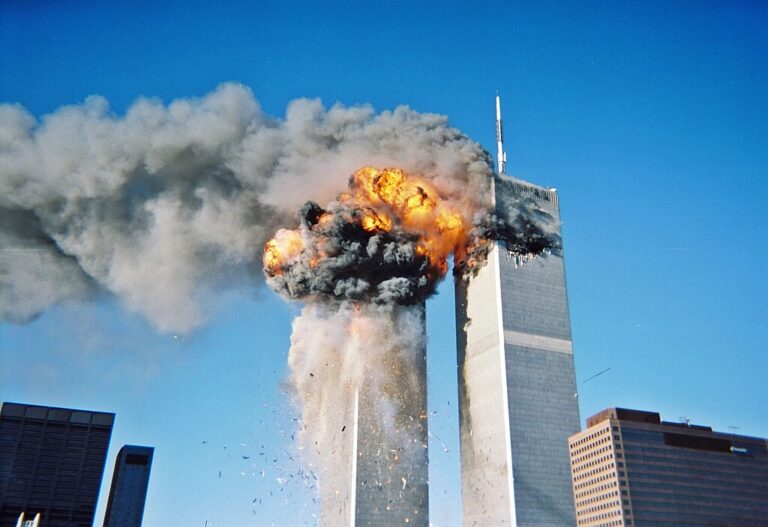

It’s while I’m doing the closing-down admin for the bar that I have a few moments to look back up at the TV and see the footage of the planes flying into the WTC towers for the first time. The almost cartoon-like plane shape left black and smoking in the side of the north tower, frozen at the angle of impact. The quiet grace and malevolence of the 2nd plane gliding into the south tower. So smooth that it seemed predestined.

“F*ck me”, I say out loud. Even this feels performative — like the kind of thing one should say in moments like these. But I don’t feel anything. How could I? All they were were images which I could not be tied to any reality I could recognise.

Later, I realise that those first bits of footage that we have been watching on repeat all evening included the tiny specks of people jumping to their deaths from the burning towers, knowing that escape was impossible and that a swift and chosen death was preferable to whatever scenes of hell must have been going on within those buildings.

At that point, no-one was asking any ethical questions about showing these images. Well — I guess the population of the world’s newsrooms were, but the rest of us were just watching, dumb.

At 11:30pm, it’s time to go home and I’m suddenly nervous. There’s no way to get back to my house in Arnos Grove in the north of the city without going on the Tube and — while we still don’t really know who is behind these attacks — one could be certain that if they hated America then they’d hate Britain too and London was guaranteed to be high up on their list of potential targets. And the Tube would be just perfect: constantly crammed with people, deep underground, no escape.

The Tube travel anxiety that thudded into my chest on the evening of 9/11 doesn’t leave me for the rest of my time in London. After a while, it fades and dulls due to sheer repetition and the force of travel necessity but comes roaring back when the Atocha station in Madrid is attacked in early 2004. London’s grace period surely had to be over now?

In fact, it almost was — London suffered its own appalling round of terrorist attacks on 7th July 2005. On the public transport network, just as I had imagined. Thankfully, I’d left the city by that time. Still — seeing the bloody carnage in places I used to pass through every day cut close to the bone. It could so easily have been one year earlier. It could have been me.

24 years have now passed and I don’t often think about the 9/11 attacks — perhaps just briefly when the anniversary rolls around again or if something else happens which triggers the memory.

About a year and a half ago I went to see an exhibition at Vienna’s Albertina museum by the artist Robert Longo, who specialises in large-dimension charcoal drawings.

His depiction of 9/11 — the outlines of two planes headed towards a single black monolith of a tower and smoke billowing, needs no explanation.

For those who remember 9/11, the silhouette of a plane would never be completely benign again.

We were there. And we remember.

—–

Image credit: Robert Levine, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons