Art as activism in a budding world power

—–

Getting into the Wilbur J. Cohen Federal Building is an experience in itself. After the strict security check, signing ourselves in, depositing our passports with the guard on reception and getting our visitor’s badges, we are finally in. At 2pm, we are collected by our guide and art expert Nick, who will be showing us the 1930s murals in the building today.

Although the building features mural cycles by other renowned artists of the 20th century, Seymour Fogel and Philip Guston, it’s the Ben Shahn murals in the passageway from the lobby that I’m here to see.

An unexpected discovery

I discovered the art of Ben Shahn (1898 – 1969) last year when I visited the Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid to see Picasso’s great war painting, “Guernica”. Anxious to wring the maximum value out of the ticket price, we explored every part of the museum, including an exhibition of Shahn’s art going on at the time entitled “On Non-Conformity”.

Shahn became popular in the 1930s when he applied his skills as a painter and photographer to create public awareness for the social issues in the USA which were important to him. Namely: the experience of immigrants in the United States as well as victims of injustice and inequality.

This sympathy for society’s underdogs flowed straight from Shahn’s own story. Born to a Jewish family in what is now Lithuania (then still a part of the Russian Empire) in 1898, he moved with his family to the USA aged 8. Living as an immigrant in New York was a formative experience that would inform and feed his art for the rest of his life.

Inspirations from home and abroad

After a brief stint refining his artistic skills in Northern Africa and Europe during the 1920s, Shahn returned to the US in 1929. In the following years, he was able to expand his skills to the creation of large-scale murals when he assisted the famous Mexican artist Diego Rivera with his controversial “Man at the Crossroads” fresco in New York’s Rockefeller Center.

Key inspiration for his oeuvre also came from a cooperation with the Great Depression documentary photographer Walker Evans. The casual street photography techniques which Shahn learned from Walker would become a defining characteristic of his own style, with the figures and motifs he captured during this period frequently featuring in his later paintings.

These experiences were not just formative for Shahn from a technical point of view: they also showed him how art could be used as a form of activism to push, and gain support for, political agendas. It could be used to demand and drive change.

A unique American style

Moving away from the European painting style which he had adopted during his sojourn on the other side of the Atlantic, Shahn began to develop his own visual style. At the same time, current social and political themes began to dominate the images he produced. The best known of these was the Passion of Sacco & Vanetti, a series of paintings concerning the controversial trial of two working class Italian Americans sentenced to death for armed robbery and murder.

Real life scenes he had documented with his camera and people he had personally met on his travels became motifs in his paintings, posters and murals. The knack he had for approaching his subjects and falling into easy conversation with them allowed him to portray them in their most natural manner, free of false poses or artifice. In this way, his art truly captures the spirits of the times, places and people of the USA in this key period of change and upheaval.

The personal connection with his subjects that Shahn managed to establish was key to his unique style and visual language, which he liked to call “personal realism”, rejecting the label of “social realism” which was all too readily applied by others.

Moving onto murals

Among his initial works in this style was a mural at the Jersey Homesteads development in New Jersey, a development set up to resettle Jewish garment workers from New York and Philadelphia as part of FDR’s New Deal. Applying the mural painting skills he had learned off Diego Rivera during his apprenticeship, Shahn created a moving pictorial chronicle of the lives of Jewish immigrants to America.

It proved to be a stepping stone to even greater things. Shahn was soon commissioned to create the mural cycle at the newly built Social Security Administration Building (now the Wilbur J. Cohen Federal Building) on Independence Avenue in Washington D.C. He was taking his political and artistic message to the administrative and political heart of the USA.

A picture of America’s domestic ambition

While, in the coming years, the attack on Pearl Harbour and the entry of the US into the 2nd World War would come to define what the US stood for externally, the murals at the new Social Security Administration Building aimed to show what the country was fighting to be domestically.

The ideas underpinning the project were taken directly from President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s address on the Social Security legislation. The president said:

‘This security for the individual and for the family concerns itself primarily with three factors. People want decent homes to live in; they want to locate them where they can engage in productive work; and they want some safeguard against misfortunes which cannot be wholly eliminated from this man-made world of ours.’

Gazing upon the murals painted by Ben Shahn as part of this project, all the strands of this vision are present. Citizens engaged in productive work and, nearby, at play. On the opposite wall, we see members of society who cannot or may no longer participate in the active workforce (children, the elderly, a nursing mother) but who are nonetheless caught by the long, supportive arms of social security.

The overall vision: a coherent and productive society where dignity in old age, illness or incapacity is ensured through the solidarity of society as a whole.

Labour as an allegory

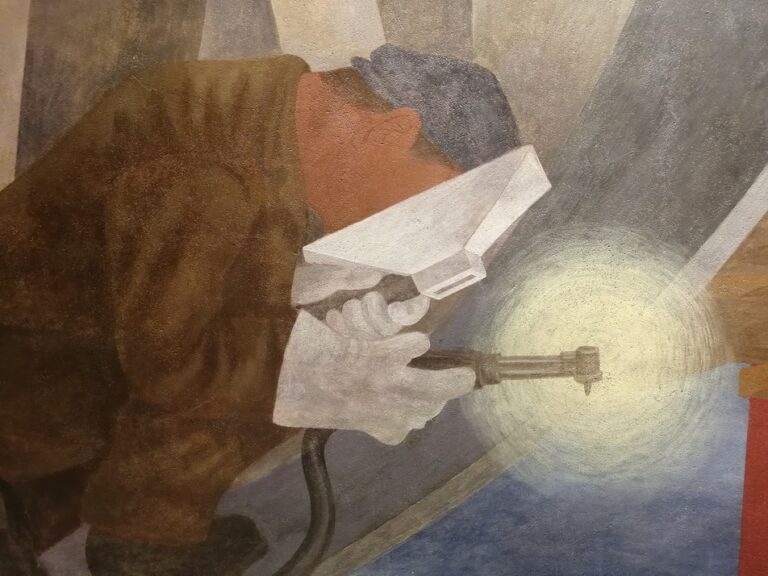

The dominant theme of the murals is of course the work and productivity which would drive the new world power and sustain its social programmes.

However, looking more closely at the murals, you see that this artistic celebration of labour is limited to the allegorical. What are the factories in the images producing? It’s not at all clear, leaving the viewer leeway to “finish the sentence” themselves.

Being familiar with the social realism art common in former Communist countries and also in my adopted home city of Vienna, it’s tempting to draw this parallel. It wouldn’t be incorrect, but clearly not what the people who commissioned the murals in the Wilbur J. Cohen Building wanted to see. Shahn was instructed not to make the murals “too European” in style: they were to be a uniquely American statement on American life.

A cheeky kickback?

Shahn’s distinctive painting style meant that this wish was fulfilled. However, he still managed to incorporate some elements of European art which he absorbed back in the 1920s as a young artist into the murals.

Consider the image below. Doors that do not seem to fit into any coherent building structure open up to reveal a work scene (again, non-specific) which in turn seems to be balanced on some form of platform. A tiny man carrying a baseball bat (a motif repeated throughout Shahn’s oeuvre), wanders away from us in the background – thematically disconnected to the rest of the picture.

It’s a scene which rejects the normal order of things, disconcerting the viewer – a technique straight from European surrealism.

Was this an open revolt – an echo from the controversy around Diego Rivera’s murals at the Rockefeller Center which he had worked on? Or was it a more subtle kickback, quiet evidence of Shahn’s strong, assertive character?

We can never know.

In any case, these murals remain a fascinating glimpse into the ambition and mindset of a budding world power and an excellent example of how art can be used as social and political activism.

—–

If you would like to take a tour of the murals at the Wilbur J. Cohen Federal Building, write to arttours@gsa.gov to arrange a date and time!

To read more about the history and the architecture of the Wilbur J. Cohen Federal Building as well as the man it was named after, click here.

—–

More from the Great Art Encounters series:

Tribute to Chopin by Jerzy Duda-Gracz

“Electric Rider” by Isolde Maria Joham

“Judith Slaying Holofernes” by Artemisia Gentileschi

“Portrait of Trude Engel” by Egon Schiele

Other related articles:

Americanisms – A British Perspective

The Battle of Flamborough Head – American History in Yorkshire

—–

Photo credits: Katharine Eyre, Christian Wagner (2024)