Killed by a Nazi officer in 1942 in his hometown of Drohobycz, Bruno Schulz left behind only a small body of writing. Yet what work it is! Dazzling, dense and intoxicating, Schulz has gained a posthumous reputation as one of the greats of Polish literature. The sense he conveys of a firm system of meaning amid a shifting, unpredictable reality offers comfort and solace in our current, turbulent times.

Bruno Schulz was born in 1892 in the Galician town of Drohobycz in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire. A sensitive young boy, he showed an early aptitude for the arts, going on to study architecture in Lviv and Vienna. Apart from these brief periods of study, Schulz travelled little — preferring to stay in the familiar surrounds of home. However, the changing socio-political landscape of the time meant that he found himself on a different kind of journey. An internal odyssey through the vibrant imaginary world that he would create and express so compellingly in his writing.

Shifting realities

Traditionally part of the Kingdom of Poland, Drohobycz became part of the short-lived West Ukrainian People’s Republic after World War I before falling to the 2nd Polish Republic in 1919. At the beginning of World War II, it was annexed to Soviet Ukraine before being occupied by German forces in 1942. Today, it lies in modern Ukraine, the spelling now changed slightly to Drohobych. A town buffeted and tossed between an Empire, two Republics, another Empire and then on to modern statehood.

Bruno Schulz himself personified the multi-layered identity that such territorial tugs of war entail. He was a Polish Jew who thought and wrote in Polish but could also speak fluent German. He was thoroughly steeped in the Jewish culture, yet apparently had no knowledge of Yiddish. This hubbub of ethnicities, identities, cultures and regimes — systems of reality coalescing, only to become unstable and break apart again — all this gave Bruno Schulz rich internal resources to draw on in his writing.

As it did for many others, too. After World War I, and the establishment of the 2nd Polish Republic, Poland saw an explosion in Avant Garde literature. The enormous transformation in Poland’s socio-political circumstances unleashed a new dynamism, with authors throwing off traditional ideas of content and form. Many began engaging in startling and creative experiments, such as Witold Gombrowicz’s cult novel, “Ferdydurke”. Bruno Schulz’s writings are very much a part of this brief, “interbellum” era.

Past the banal to the Sublime

In his work, Schulz makes no mention of the real-world events and changes going on around him. However, it conveys an acute sense of the impermanence and flimsy nature of reality that such turbulence must impart. For him, reality was a disappointing container or sham that concealed a true, pure essence of things beneath. In the short story “The Book”, he writes:

“There are things that cannot ever occur with any precision. They are too big and too magnificent to be contained in mere facts. They are merely trying to occur, they are checking whether the ground of reality can carry them. And they quickly withdraw, fearing to lose their integrity in the frailty of realisation”.

To Bruno Schulz’s mind, the writer’s job was to use the power of the poetic to pierce the grey veil of reality and liberate the Sublime from beneath. The writer may thus turn his poetic gaze to any scrap of degraded reality (referred to by Schulz as “tandeta”, roughly translating to “trash” or a “cast-off”) and turn it into object of wonder; a key to the Sublime. In Schulz’s vast imagined world, there was no border between one state and the other. In his writing, the perceived reality spills straight over into fantasy. The everyday and the banal is mythicised and takes on an inherent magical potential.

It is exactly this possibility of an underlying system of meaning and truth amid a chaotic and uncertain present that makes Schulz such an appealing author for our times. Just as Schulz found himself caught up in a maelstrom of world events and competing cultures and ideas, our post-1945 order is crumbling while new structures attempt to form. The internet plunges us all headfirst into a sea of different possibilities and views. It’s easy to feel overwhelmed, insecure in our identity and cut adrift. Amid that chaos, Schulz’s writings offer us comfort. It teaches us that – if we look hard enough and with enough of a sense of wonder – a stable framework of meaning can still be discerned in the disorder.

Bruno Schulz: a lost genius who continues to inspire

Bruno Schulz’s life came to a tragic end one day in November 1942. On the way back from buying bread in Drohobycz, the Nazi officer Karl Günther shot him dead. Allegedly as an act of retribution for Schulz’s protector, Felix Landau, having killed Günther’s “own Jew”.

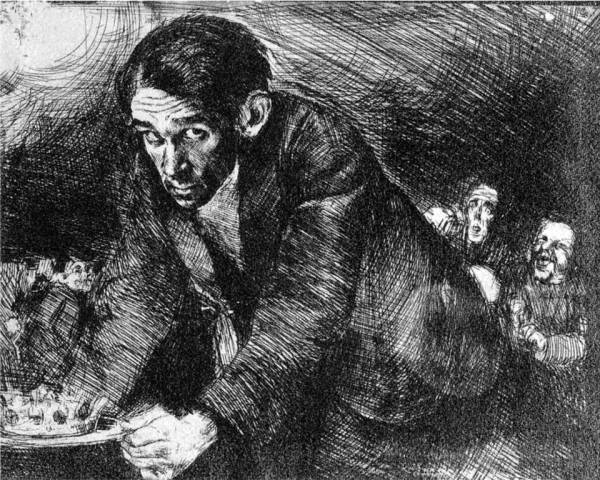

Schulz’s star burned across the Polish literary heavens for only the briefest time. Many of his papers, including his final (unfinished) work, “The Messiah”, were lost forever. All that remain are the compositions “Cinnamon Shops” (Sklepy Cynamonowe) and “The Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass” (Sanatorium Pod Klepsydrą), a number of his distinctive drawings and a couple of other short stories. But what a legacy to have left behind! One wonders what this curious, withdrawn man could have achieved had he lived on.

To this day, Schulz’s work continues to captivate, enchant and inspire. As David A. Goldfarb writes in his introduction to the Penguin Classics version of “The Street of Crocodiles and Other Stories”, Schulz’s influence on post-war writers varies in its nature. Some have adopted his leitmotifs and compositional methods to continue the Avant Garde tradition. Jewish writers such as David Grossman see in Schulz’s work a connection to a lost world of European Jewry, wiped out by the horror of the Holocaust.

Others, like Salman Rushdie, tap into the sense, inherent in Bruno Schulz’s work, of a metaphysical system of meaning under a shattered reality. This feeling of being “rooted in displacement” gives the writer an anchor as they sort through the disarray to make sense of the real world. For readers, it is a comfort at a time when many of feel like there is only disorder.

—–

Related articles:

Great art encounters: Picasso’s “Guernica”

—–

Illustration credits: Self portrait & illustration by Bruno Schulz, public domain via Wikimedia Commons