A trip to Madrid to meet a 20th century masterpiece

—–

Damn. I’ve seen it. That wasn’t meant to happen.

I’m in the Museo Nacionale Centro de Arte Reina Sofia in Madrid on a chilly Friday morning in November. Ready at last to see Picasso’s monumental, wall-filling epic “Guernica”.

Knowing I was getting close, I start glancing around the room I’m in and the ones surrounding it to see if I can find The Other Half. He’s here somewhere and I want to be with him when we meet the great masterpiece.

I had it all thought out: I was going to approach the painting with purpose, only allowing myself to look up when I would have a clear view of it – like lifting a bride’s veil on her wedding day. There was going to drama. There was going to be impact.

Now I’ve messed up my own script by inadvertently catching a glimpse of the painting through the doorway. Oh well, it can’t be undone now.

I decide the Salvador Dali I’d been looking at can wait and give in to the pull of the painting in the next room. And there I stay for the next 20 minutes, completely under its spell. Over the next 2 hours, I return twice more, only turning my back for the final time when I feel like I’m saturated with the sight of it.

A primal scream of a painting

Not many works can make a Dali painting seem like a minor distraction. But there again, not many paintings are like Guernica.

Even the words “epic” and “monumental” seem to come up short when trying to accurately describe this work and its effect on the viewer.

Measuring 7.75m x 3.5m, Guernica takes up an entire wall of the room in which it is exhibited. It’s impossible to ignore and impossible to pass by without stopping to look. The painting doesn’t ask for your attention – it demands it. And doesn’t let it go.

Stepping into a political and diplomatic vacuum

In painting “Guernica”, Picasso was on a mission: to wake the world up to the horrors of the bombing of the small Basque town of Guernica by the Nazi Luftwaffe and fascist Italy’s Aviazione Legionaria in 1937, killing several hundred men, women and children.

Although the attack caused outrage around the world, the fraught geopolitics of the time meant that serious consequences for the perpetrators were doubtful. Fearing that any kind of retribution would escalate the civil conflict into another full-blown World War, Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Germany, the Soviet Union and a number of other countries agreed not to assist either the Nationalists or the Republicans. However, with the blatant violations of the pact by Germany and Italy in Guernica, it became apparent that non-intervention had become a performative matter: words with no effect beyond the paper on which they were written. Still, the allies hung back.

With politics and diplomacy hamstrung and uncertain, art stepped into the fray. Picasso, usually resolute in his avoidance of the political in his work, was so outraged by the appalling slaughter of his countrymen in Guernica and the timid international response that he decided to wade into the fray, with his paintbrushes as weapons.

Already working rather half-heartedly on some sketches for a mural to be exhibited in the Spanish pavilion at the 1937 World Expo in Paris, he abruptly changed course after the poet Juan Larrea implored him to make Guernica his subject. Incensed at the injustice and atrocity, Picasso began work on the painting which would become central to his oeuvre.

For him, it was all or nothing. This exceptional dip into the fraught field of political painting had to land perfectly, and have maximum impact – both in terms of the creative process and the finished work itself.

Like a man possessed

Astoundingly, Guernica took only 35 days to complete. Contemplating the sheer size of the picture, one can only begin to imagine the fury with which it flowed out of its author’s imagination and onto the canvas. Mistakes, imperfections, dribbles of paint have been left unremedied – as if in testimony to the urgency of the painting process.

Besides the political, Guernica also marked other breaks in Picasso’s normal approach to painting. Firstly, he invited the French photographer Dora Maar (who would become Picasso’s lover and muse) to capture the painting at various stages of completion. These photographs are said to have emboldened Picasso to make Guernica a colourless work, reminiscent of the black and white press photography which had chronicled the civil war for international audiences.

Generally a solitary painter, Picasso now invited several influential figures into his studio while he worked on Guernica. Every opportunity to communicate and spread the antifascist, antiwar message of the painting was seized and exploited to the full.

War art brought into the 20th century

With Guernica, Picasso took war art and recast it for the age of mass death by machine.

While echoing classic paintings such as Peter Paul Rubens’ “Consequences of War” as well as Michaelangelo’s Pietà in the motif of the woman holding the body of her dead child, Picasso’s distinctive abstract style and harsh monochrome colour scheme stamped his own, unmistakeable signature on the genre.

However, to say that Guernica was conceived and realised as a statement on modern warfare, there is only one symbol of modern technology in the entire painting: the lightbulb hanging over the violent scene of death and suffering. And it isn’t the source of light in the painting – that’s coming from the oil lamp to its right. Perhaps a statement by the artist that the machines of modernity have not brought humanity; only death, destruction and a loss of hope.

On world tour

From the World Expo in Paris, Guernica was taken off its frame, rolled up, and sent on tour all around the world. Curious audiences in UK, Germany, Sweden came to bear witness to the epic work before it departed for the USA, where its exhibition helped to raise money for Spanish refugees.

At Picasso’s request, the painting was kept in the safekeeping of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, defying Franco’s requests to bring the painting to Spain. Picasso had sworn: Guernica would never be taken to Spain unless and until freedom democracy were reestablished there. To give in to the dictator’s wishes would have been to undermine the antifascist message at the very heart of the work.

A message which was still capable of stirring up intense feeling. Indeed, in 1974, it was vandalised as it hung in MoMA. Tony Shafrazi, an artist of Iranian extraction, sprayed the words “Kill Lies All” across the canvas in red paint in front of shocked onlookers.

Shafrazi claimed the act of vandalism was a form of performative art in itself – but was also believed to have been protesting the release on bail of a U.S. Lieutenant who had been convicted for his part in the My Lai massacre during the Vietnam war.

Shafrazi’s act caused uproar and long-lasting memories: his spray-paint effort fortunately did not. Due to Guernica’s heavily varnished finish, the red paint was able to be completely removed. No trace remains.

Guernica finally goes “home”

The Franco regime came to an end in 1975 and Spain finally transitioned to a democracy. Even though Picasso was no longer alive (he had died in 1973), it was now clear that there could be no objections to Guernica being handed over to Spain, the country of whose heritage it now formed an indelible part.

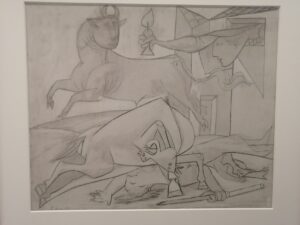

However, MoMA was reluctant to part with one of the largest jewels in its crown and tried to block Spain’s requests. Only in 1981 did it finally make the journey to Spain, where it is now displayed in the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, along with a number of preparatory sketches and Dora Maar’s photos of the work-in-progress.

The enduring power of “Guernica”

Even though painting has not been attacked or vandalised in recent times and is no longer displayed behind bulletproof glass, that doesn’t mean its power has faded in any way. Its image – even in replica – has a silent, but menacing force and authority that extends far beyond the original subject matter and has humbled some of the world’s most powerful men.

In 2003, Colin Powell, the then Secretary of State of the US was to speak in front of the UN Security Council, arguing in favour of going to war in Iraq. The tapestry of Guernica which hung at the back of the lectern where Powell was to speak was covered for the speech. Some argue that the harsh black and white and frantic lines of “Guernica” did not offer a suitable background for a TV recording or press photos. Other sources say that George W. Bush wanted the tapestry covered so as not to undermine the case for war which Powell intended to make.

Whatever the motivation, the concealment spoke its own language. And, looking back on that now – Picasso’s painting seems to have provided better advice to us than the most powerful men in America. No wonder they feared it.

—–

More from the “Great Art Encounters” series:

“Judith Slaying Holofernes” by Artemisia Gentileschi

“The Birth of Venus” by Sandro Botticelli

“The Slav Epic” by Alphonse Mucha

“Portrait of Trude Engel” by Egon Schiele

—–

Photos taken by the author