As I wrote a short while ago, my new year’s resolution for 2023 is to learn one poem a month off by heart. Asking friends and relatives to provide me with their suggestions, I put together a list of 12 poems and selected the first one at random. First up? “If — ” by Rudyard Kipling.

Here is a link to the text of “If-” in full. For those who would like to listen to the poem, here is a link to the lovely Ralph Fiennes reciting it.

The Britishest of all British poems?

In 1995, the British public voted “If — ” by Rudyard Kipling its favourite poem. Hugely popular, it gained twice as many votes as the runner-up, Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalott”. Small wonder — as the best-known lyrical expression of the Victorian values of stoicism, self-discipline and reserve, many people consider “If-” to capture the essence of Britishness. That is to say: the famous stiff upper lip.

So firm is “If”’s place in the British cultural imagination that excerpts from it are displayed in prominent public locations in the UK. The lines “If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster/And treat those two impostors just the same” stand above the entrance to Centre Court at the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club, where the finals of the Wimbledon tournament are played each year. A call to equanimity so universal, it can reach out and touch everyone. From top tennis players about to play the match of their lives to schoolchildren learning how to deal with defeat and setbacks.

Life & times

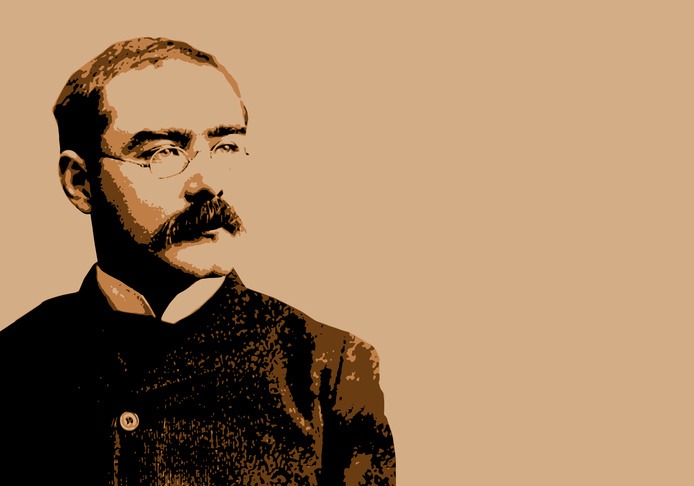

Rudyard Kipling was born on December 30, 1865, in Bombay (now Mumbai) in India. He spent his early childhood years on the subcontinent, whose rich culture profoundly influenced his later writing.

Besides several famous poems (including “If-”, “The White Man’s Burden” and “Gunga Din”), Kipling also wrote a number of novels, such as “Captains Courageous” (1897), “Kim” (1901), and “The Light That Failed” (1890). His best-known work, however, is and remains “Jungle Book”. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1907.

Kipling was an enthusiastic advocate of British imperialism as well a staunch supporter of the war effort during WWI. Although the tragedy of losing his son John in the Battle of Loos in 1915 may have caused him to reflect on his beliefs somewhat — he was convinced that Britain was superior and that its people had a calling. That was: to fight for freedom and civilisation — and bring these values to the furthest corners of the world.

Rudyard Kipling died on January 18, 1936, in London, England.

“If-” by Rudyard Kipling: a classic of universal appeal

Although his imperialist views have now turned him into something of a posthumous cultural pariah, Rudyard Kipling remains a key figure in the pantheon of British literature. To push him entirely to the sidelines of study and discussion in the modern world is to wilfully ignore the contribution he made to his genre.

While it is never possible to completely disentangle the author’s person from their work, one should certainly try and consider “If — ” quite apart from Kipling’s personal and political views on empire and white supremacy. The poem offers a universal set of guidelines for how to live a virtuous and successful life. It encourages the reader to maintain their composure and rationality in the face of adversity, and to have self-confidence and self-belief. The words call on us to be patient and persistent, to be honest and truthful, and to seek knowledge and wisdom. It is an address to all.

The series of commands set out in the poem, its call to strive for higher ideals beyond oneself — are almost prayerlike. Indeed, reading them back to myself again and again while learning the poem transformed it into a kind of secular incantation. It felt comforting: as if by reciting the words I was getting in touch with something greater; something shared with many others.

Because the poem originates from, and is deeply rooted in, British culture — one could also conclude that it does allow the reader to feel connected to other Brits. It might be said to encapsulate the shared identity, offer a direct experience of that identity, and call for its perpetuation.

What IS Britishness, actually?

But — was the idea of Britishness as immortalised by Kipling in “If — ” ever a thing of truth? Or just a figment of the collective imagination, romanticised and elevated to the status of incontrovertible historical fact through the written word? And – even if that character trait did once exist on a broad scale among the British people — was it such a desirable thing? Or did it do people more harm than good? Moreover -is it still the core of the national character today?

Quite where this idea of the stuff upper lip came about, no one is really sure. Kashu Ishiguro, the Japanese-British author of “The Remains of the Day”, is convinced that the drive to emotional reserve was a result of empire. Members of the upper and upper-middle classes were drilled to present a cool, calm exterior to their colonial subjects, enforcing the narrative of a superior race entitled to authority. This attitude was further hardened by the trauma of the two world wars. When there is so much hardship, navel-gazing and letting one’s emotions show seem like an inappropriate luxury.

A new, emotional era

Many Brits of my generation were brought up by Boomer parents born just after World War II. They still subscribed to the values of stoicism and fortitude shown by their parents and didn’t set great store by open displays of emotion. We looked to them and learned.

Yet it is the right of every generation to question the ways of the ones who went before — and Millennials are no different. The death of Princess of Diana is commonly seen as a kind of watershed moment in the nation’s relationship to its own emotional interior. Looking back, the outpouring of feeling witnessed at that time was the starting shot for a more open approach to mental health and one’s feelings. To the delight of some — and the chagrin of others.

We Millennials were only teenagers at that strange, tragic time. Old enough to remember the days of chillier demeanours, yet young enough to absorb the mores of the new, more emotional era. We understood the value of the stiff upper lip — but also knew to question it and see alternative ways of being.

Too much of a good thing?

In a way, that loosening of the national emotional corset has been a thoroughly good thing. Mental illness is now largely destigmatised, enabling people who are struggling to speak out and obtain help. “Pull yourself together and get on with it” as a piece of advice sometimes doesn’t cut it.

But most of the time, it does.

The pendulum which started to swing away from reserve to openness in 1997 has now gone too far. Feelings are starting to take on the quality of facts. The emotional is starting to take precedence over the rational, and the urge to look inwards is nudging out the idea of looking outside – and getting over – oneself.

If Kipling were to spend a few days in modern Britain (or any other Western country for that matter), he might not encounter people who had lost everything “And never breathe a word about [their] loss”. Instead, he might meet people who have taken risks, lost everything — but then spend the rest of their lives moaning and refusing to take any responsibility for their mistakes. He’d probably see a few of them making a fortune by peddling their supposed victimhood on social media. I think he’d be horrified.

To some, “If-” might seem like an uptight relic of yesteryear. To me, it looks like the perfect antidote to a world losing itself in narcissism, lucrative victimhood and emotional incontinence.

—–

Related articles:

The Poetry Project – from new year’s resolution to revivifying an ancient art

10 British English words of Indian origin

Augustus Gloop HAS to be fat – sorry, snowflakes!

Whither Brand Britain? Kiwi shoe polish bids goodbye to the UK

—–

Photo credit: pict rider – adobe.stock.com