A monumental work that helped to create a national consciousness

—–

Yesterday, a dream of mine came true. I finally got to see all 20 canvases of the Slav Epic by the Czech artist Alphonse Mucha.

The chateau in the tiny Czech town of Moravský Krumlov in Southern Moravia (population: 5,700) seems like an unlikely venue for such a famous art ensemble – you have to take a train right out into the countryside from Brno to get there. And by “countryside”, I mean proper cows-grazing-wizened-old-people-out-digging-vegetable-patches countryside. No-one speaks much English or German out in this neck of the woods so I have to crack out my (very) rudimentary knowledge of Czech to buy bus tickets from the station.

I’d seen three or four of these huge paintings as part of another Mucha exhibition in Brno in 2018, but never the whole cycle. This was going to be an experience of an entirely different dimension. It’s with feelings of giddy excitement that I jump out of the bus one station too early and end up having to walk up the hill to the chateau.

A long-time love affair

In a way, this feels like the fulfilment of a prophecy. I fell in love with Mucha’s work aged 15 while doing my art GCSE. Way before I ever thought of moving to the German-speaking area, way before I moved to Austria, and long before I fell in love with the Czech Republic.

As part of the final piece of GCSE coursework, we were required to choose an artist and study their oeuvre in depth, culminating in a larger work inspired by it. I’d already developed a penchant for art nouveau during the first year of the course when I’d spent time studying the art of old Vogue magazine covers. And, when it comes to art nouveau, it can never be long before the name Alphonse Mucha comes up.

With their distinctive floral borders and goddess-like female figures in jewelled and flowing robes, Mucha’s works really caught my attention. I was happy to spend time in his elegant world and started to find out more about this classic fin de siècle artist. It was the start of a long-term love affair.

The Slav Epic – Mucha’s opus magnum

Of course, it is impossible to talk about the work of Alphonse Mucha without referring to the Slav Epic. Every book or article about him will include it.

The Slav Epic was his life’s work and his opus magnum; the one in which his heart was clearly invested – and for which he even took political risks.

The cycle comprises 20 massive canvases depicting the story and the mythology of the Slavs through history. Painted between 1910 and 1928, they show the Slavs as an extended family of peoples with a common, entwined history. Separate and distinct, yet bound in destiny and desiring peaceful coexistence.

While Mucha’s commercial posters and advertisements served rather banal and short-term goals, the Slav Epic had ambition. It was to be nothing less than a contribution to the construction of a national identity and consciousness among his fellow Czechs – and the wider Slavic family.

Finding the means

Mucha nursed the idea of the Slav Epic for a number of years but was unable to commence the project due to financial constraints. His commercial work brought income – but not enough to give him the space and time he needed to devote himself to such a huge, historically weighty project. He needed a patron.

It was during one of several trips to the United States in the early years of the 20th century that he made the acquaintance of Charles Richard Crane, a wealthy Chicago industrialist. Crane had developed a deep interest in the Pan-Slavic movement after meeting Tomas Masaryk, and agreed to finance the project.

The door to Mucha’s life project was finally open – and no effort was to be spared in achieving the desired impact and message. He began by visiting various countries relevant to the project as well as consulting historians about the course of events he wanted to depict. In 1910, with his research complete, Mucha rented rooms in the castle in Zbiroh and began work in earnest.

Setbacks in completion

Through war, through the fall of the Habsburg empire and the establishment of the new state of Czechoslovakia, through the rising political turbulence of the 1920s – Mucha kept working.

Finally, in 1928, the paintings were completed and exhibited together in Prague, the glittering capital of the brand-new country of Czechs and Slovaks. Mucha bequeathed the paintings to the city: on the condition that a suitable venue be built to house them.

Yet that dream would soon be forgotten amid the turmoil would befall Czechoslovakia just 11 years after the Slav Epic was completed. In March 1939, the Nazis absorbed the Czech lands of Bohemia and Moravia into the Third Reich, splitting the fledgling country apart and plunging its people into chaos, fear and oppression.

A long tumble into obscurity

As a well-known Czech nationalist and freemason, Mucha was a prime target for the Nazis who were anxious to neutralise any resistance to their regime among the local population. He was arrested and interrogated by the Gestapo. He was released after several days, but his health irreparably damaged by the ordeal. The now elderly Mucha contracted pneumonia shortly afterwards and died in July 1939.

It was a mark of the respect and esteem he enjoyed among the Czech people that around 100,000 people attended his interment in the Vyšehrad cemetery in Prague – the final resting place of renowned Czech writers, composers and other leading cultural figures. At the time, large gatherings of people had been prohibited by the Nazis and attendance came with a considerable personal risk.

During the war, the paintings of the Slav Epic were rolled up and hidden to prevent them falling into the hands of the Nazis who no doubt would have destroyed such overt symbols of Slavic culture, which they considered inferior.

Even with the war over, Mucha’s work would tumble further into obscurity. Under the Communist regime which took over in Czechoslovakia in 1948, his elaborate and decorative style was considered outdated and bourgeois – at odds with the social realism preferred by the new establishment.

The Slav Epic remained in storage until 1963, when the paintings were moved to the tiny town of Moravský Krumlov, close to Mucha’s hometown of Ivančice. There, they were put on display in the crumbling old chateau, a property which once belonged to the aristocratic Liechtenstein and Kinsky families.

And there they are now – for the time being at least.

Admiring the Slav Epic

Entering the exhibition rooms in the chateau occasions an astonished gasp. How big the paintings are – how could Mucha possibly have kept perspective on them while working?

And the detail! Each picture is an ocean of activity – masses of people, movement, flowing fabrics, lively faces showing fear, passion, shock, disgust…and the artist has paid loving attention to every single one.

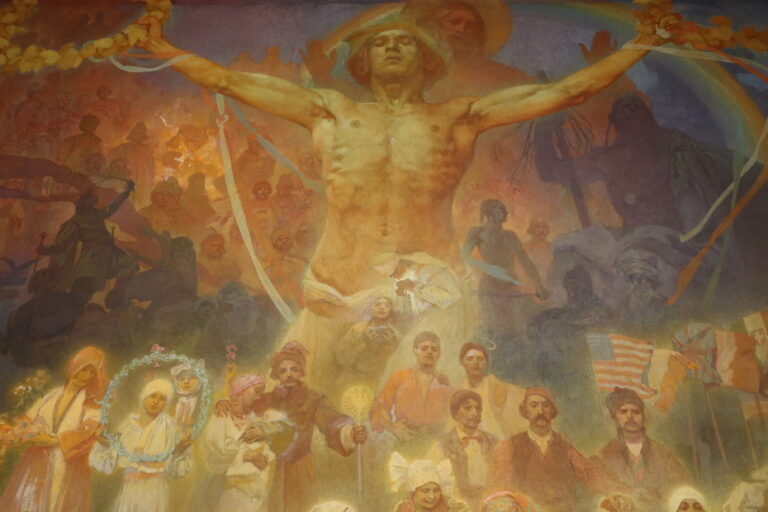

In the Slav Epic, real and spiritual worlds collide, with humans sharing the space with mythological figures, Gods and allegories. Some even exceed the outer boundaries of the picture, creating the impression that they are stepping out of the picture towards us. When you stand directly before the larger pictures, they literally fill your field of vision: it is easy to feel like you are in on the action. Perhaps this was the intention: Czechs and other Slavs contemplating the paintings were meant to feel as though they are part of this incredible story and feel stirred and a sense of belonging.

Beginning with a depiction of the Slavs in their original homeland, cowering to avoid attack from marauding Germanic tribes, the epic moves us through the settlement of Rügen and the worship of pagan gods before addressing the conversion to Christianity in the 9th century. We are introduced to great men of Slavic history such as the Bohemian King Ottokar II and the Serbian Stefan Dušan, gaze upon scenes of destruction during the Hussite wars and learn about Czech rebellion against papal control.

Moving onwards, allegorical scenes depict the nationalist movements of the 1800s and the abolition of serfdom in Russia as old imperial structures dissolved in the early years of the 20th century. In the final scene, the Slavic spirit rises up as a Christ-like figure, radiating strength and optimism for a new era of Slavic self-determination in the post-1918 world.

Back to Prague?

Although I enjoyed my two hours admiring the Slav Epic in the old chateau, I couldn’t help but think that this is not the best space for its exhibition. The lighting is far from ideal. Some of the rooms are too small. The paintings jostle against each other, reducing their impact.

Indeed, the authorities in Prague have been trying to secure the transfer of the paintings for some years, citing Mucha’s own bequest to the city. The Moravians and Mucha’s own descendants have steadfastly refused to concede: the condition of the bequest – that suitable premises for the exhibition of the epic are found/built – has never been met.

The protracted legal tug-of-war between capital and province that ensued excited great feeling far beyond the artistic community. It even echoed right up into the upper echelons of the Czech political establishment, with the former president Václav Klaus throwing his support behind the people of Moravský Krumlov. The parties now seem to be working towards an amicable solution for moving the paintings to Prague, but the details are uncertain.

The story of the Slav Epic is not yet over.

—–

More from the “Great Art Encounters” series:

“The Birth of Venus” by Sandro Botticelli

“Portrait of Trude Engel” by Egon Schiele

“Tribute to Chopin” by Jerzy Duda-Gracz

“Electric Rider” by Isolde Maria Joham

—–

All photos taken by the author.