You can never have enough nerdy information, imho.

—–

2024 has been my American year. Not just because I went all-out on watching the presidential election for the first time. We also went on holiday to Washington D.C. for 10 days in October and I wanted to absorb as much US history as possible beforehand to get the most out of our visit.

In amongst the vast amount of information I inhaled while at home in Europe and during our stay in D.C. were some lovely curiosities. And I like to collect quirky little facts like magpies like to collect shiny objects – I pick them up, carry them home and hoard them so I can get them out again in the future, turning them over and over in my hand.

And, seeing as you’re here, I guess you like random US history facts too. I’m only too happy to open up my Big Box of Nerdiness and share them with you.

—–

1. When a cup of tea is more important than military victory

Everyone with even the most basic knowledge of American history will have heard of the Boston Tea Party of 1773, when American colonists dumped 342 chests of tea belonging to the British East India Company into Boston Harbour to oppose the Tea Act and, more broadly, having taxes imposed on them by a parliament in which they were not represented. It was one of the key events on the path towards the American Revolution and independence.

While the Boston Tea Party is the best-known example of tea playing a pivotal role in the establishment of the USA, those unassuming little leaves were also central to other events which determined the course of America’s emancipation from their colonial overlords.

Stopping for a leisurely cuppa

During the Battle of New York in 1776, the British army under William Howe landed at Kip’s Bay on 15th September. The inexperienced American troops stationed there scattered quickly, allowing the British to land almost unopposed.

With the Continental Army split between the southeast of Manhattan island and Harlem Heights to the north, the British looked certain to isolate the two groups of troops. This would have crucially weakened the Continentals in the campaign to defend the “key to the Continent”.

The reason this didn’t come to pass was because the British moved westwards too slowly, even stopping to perform that most British of tasks: brewing themselves a cup of tea [1].

This leisurely pace of advance allowed George Washington and his men to escape Manhattan Island and rejoin the other troops at Harlem Heights from where they could attack the British in a more consolidated fashion. It stopped Howe and his men from moving north for two months.

Language note (because I love to geek out on that too): in British English, this kind of messing around with useless tasks when you don’t have the time to do so is called “faffing” or “faffing around”. Basically, if your army faffs, you should worry.

[1] “A Leap in the Dark – The Struggle to Create the American Republic” by John Ferling, p. 186

2. On the perils of patriotic fervour

No less than three presidents of the United States have died on the 4th July, Independence Day.

John Adams and Thomas Jefferson provided the ultimate proof of their commitment to the American project by dying within hours of each other on 4th July 1826. James Monroe followed their example by popping his clogs on 4th July 1831.

Zachary Taylor had a jolly good go at joining this ultra-elite Dead Patriots Society but didn’t quite make it. He became ill after eating cherries and milk at Independence Day celebrations in Washington D.C. on 4th July 1850 but hung on until July 9th when he died of an unidentified gastrointestinal complaint.

The moral of the story: go easy on the patriotic zeal! It could be the end of you.

3. Upon my honour…or honor?

The Jefferson Memorial in Washington D.C. stands above the Tidal Basin, its radiant white dome visible from afar.

The inside walls of the memorial bear four inscriptions of words attributed to Jefferson. On the southwest wall, words taken from the beginning and end of the Declaration of Independence (a text largely authored by Jefferson) can be seen:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, that to secure these rights governments are instituted among men. We…solemnly publish and declare, that these colonies are and of right ought to be free and independent states…And for the support of this declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine providence, we mutually pledge our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honour.”

Hold on just a minute! As a speaker of British English and lifelong language geek, I couldn’t help but notice that final word (look to the bottom right of the picture). Why was it spelled in the British way, with a “u” when, in the final version of the Declaration of Independence, it is spelled “honor”, as is the standard in US English?

The reason for this little tic of Britishness at a key American site is this: at the time when Jefferson drafted the declaration of the independence, US English had not yet been standardised. Spelling was more fluid, with British spellings still being used interchangeably with their American equivalents.

Since the designers and historians who worked on the monument were anxious to preserve the authenticity of Jefferson’s use of the language in the inscriptions, they chose to stick with the British spelling of “honour”.

Extra geek points: sharp eyes will also notice that the inscription featuring words from the Declaration of Independence refers to “inalienable rights” whereas the final version of the declaration of independence refers to “unalienable rights”. There is no difference in the meaning of these words and they both still appear in the Merriam-Webster dictionary, although “inalienable” tends to be used more widely these days.

The difference in spelling in the final version of the Declaration of Independence as compared to drafts written by or on behalf of Thomas Jefferson may be down to him not being in charge of the printing of the document: that was John Adams. Those minor changes may have been made at his request.

4. A southern tradition

Following the custom of many Americans to style themselves using the initial of their middle name, Harry Truman, America’s first president in the postwar era, added the initial “S.” between his first name and surname.

However, this “S.” was not an abbreviation of a particular name. It was added to honour both of his grandfathers, Anderson Shipp Truman and Solomon Young. Truman was born in the state of Missouri in the South where this naming convention was customary at the time.

5. How the USA got its national anthem

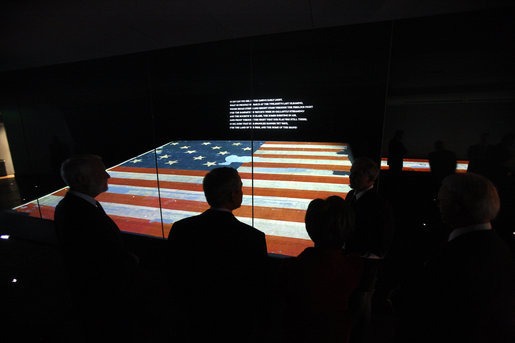

One of the highlights of our trip to D.C. was seeing the “original” star-spangled banner at the Museum of American History, i.e. the very flag that inspired Francis Scott Key to write the modern national anthem after seeing it fluttering over Fort McHenry after British bombardment in 1812.

It is one of the museum’s most precious and special exhibits. In fact, the guide I spoke to in the lobby told me that if the museum caught fire, that is what they’d save first. I don’t doubt it, it is a real treasure and part of the very soul of the nation.

This massive flag (measuring 30ft by 34ft) bears 15 stripes and 15 stars for each of the states which were in the Union at the time it was made (see photo below).

It was made by Mary Pickersgill, a Baltimore widow who was frequently commissioned to sew flags for the military and for ships. She was assisted by her daughter, nieces and African American servant, Grace Wisher. Pickersgill’s mother may also have helped. They were able to complete the work in about six weeks, but had to move the project outside of their house to a nearby brewery to complete it because it was so big.

“The Star-Spangled Banner” was a favourite among patriots and the military for many years before it was made the national anthem of the United States of America on March 3, 1931 by President Herbert Hoover.

By the way: it is my personal conviction that Whitney Houston’s performance of The Star-Spangled Banner at the 1991 Superbowl will never be bettered. I’m not even American and I still get tearful watching it 33 years later. She made it look so easy! Quite simply one of the best singers of all time.

6. The contents of a powerful man’s pockets

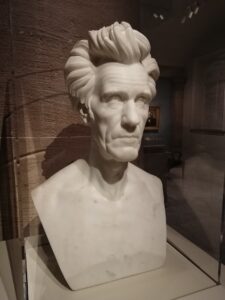

As one of the most important figures in American history, a certain myth has grown up around Abraham Lincoln. His belongings have become relics, his monument in Washington D.C. a national shrine.

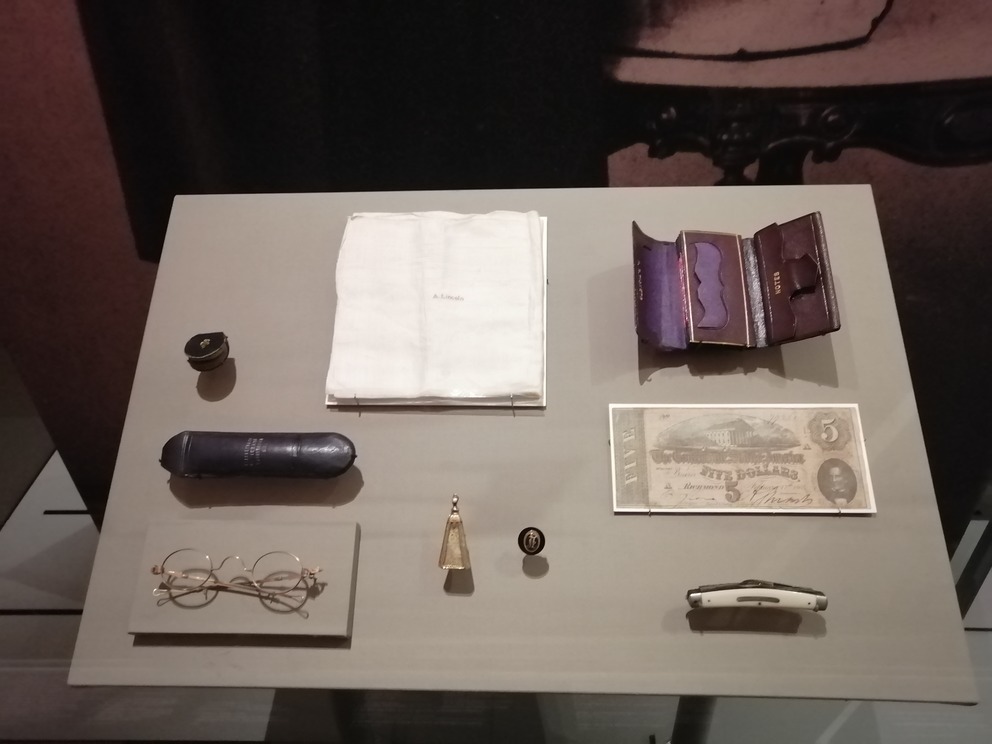

When Lincoln was shot at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. on April 14, 1865, he was taken to Petersen’s House across the road, where he died at 7:22am on the 15th. The contents of the president’s pockets were collected and handed over to his son, Robert Todd Lincoln.

These objects – so touching in their banality – were kept in the family for the next seventy years before being given to the Library of Congress where they were finally put on display in 1976. It is unusual for the Library of Congress to display personal items, but an exception was made for this small ensemble of Lincoln’s pocket litter. The then Librarian of Congress Daniel Boorstin explained that their exposure would help to humanise a man who had become “mythologically engulfed”.

A president’s pocket paraphernalia

At the time of his death, Abraham Lincoln, the 16th President of the United States of America and surely one of the most remarkable men in its history, was carrying:

- one pair of gold-rimmed spectacles with sliding temples and with one of the bows mended with string;

- one pair of folding spectacles in a silver case;

- an ivory pocket knife with silver mounting;

- a watch fob of gold-bearing quartz, mounted in gold;

- an oversize white Irish linen handkerchief with “A. Lincoln” embroidered in red cross-stitch;

- a sleeve button with a gold initial “L” on dark blue enamel;

- a leather wallet, including a pencil, lined in purple silk with compartments for notes, U.S. currency, and railroad tickets. The wallet held a Confederate five-dollar bill and eight newspaper clippings.

(The clippings were from papers printed immediately before Lincoln’s death, containing complimentary remarks about him written during his campaign for reelection to the presidency. The Confederate five-dollar bill may have been acquired as a souvenir when Lincoln visited Petersburg and Richmond earlier in the month.)

You see: even the most legendary of men aren’t immune from accumulating everyday debris and detritus in their pockets.

7. Andrew Jackson, Part 1: I challenge thee to a duel

Andrew Jackson, the 7th President of the United States of America was (and remains) a controversial figure. He was known to be hot-tempered and a streak of violence and aggression runs through his entire life and legacy. He is the only POTUS to have killed a man in a duel.

In 1806, Jackson killed Charles Dickinson, an attorney and slave trader, in a duel after a protracted quarrel. The feud originally arose over a bet on a race between two horses owned by Jackson and Dickinson’s father-in-law, Joseph Erwin. Dickinson was drawn into the row, publicly insulting Jackson and – allegedly – his wife Rachel too.

Jackson, adhering strongly to the prevailing southern culture of honour, could not leave these remarks without response and eventually issued a formal challenge to a duel, which would take place on May 30th 1806 in Kentucky.

Dickinson, an excellent marksman, shot first and hit Jackson in the chest. Incredibly, Jackson remained standing despite having sustained a severe injury and returned fire, fatally wounding Dickinson.

The bullet remained stuck in Jackson’s chest for the rest of his life. It was a souvenir of an episode which cemented his reputation as a man of extreme toughness and honour, who represented the intense and violent nature of personal and political conflicts of the time.

8. Andrew Jackson, Part 2: Tough, but tender

As we have seen, Andrew Jackson was prepared to resort to violence to defend his own and his wife’s honour. However, his great love for his wife did have more positive effects.

Rachel Jackson died in December 1828, just weeks before her husband’s inauguration. Devastated, and believing that Rachel’s death had been hastened by the vitriol of the election campaign, Andrew Jackson is said to have had a cutting of Rachel’s favourite magnolia tree brought to Washington D.C. from their home at The Hermitage in Tennessee. He planted it in front of the White House’s south façade, where it remained until being cut down in 2017 due to its poor condition.

—–

Related articles:

Great Art Encounters – Ben Shahn Murals at the Wilbur J. Cohen Federal Building

Americanisms – A British Perspective

Megyn Kelly – 8 reasons why she’s my role model

—–

Photo: US flags flying at the Washington monument, Washington D.C. (Katharine Eyre © 2024)