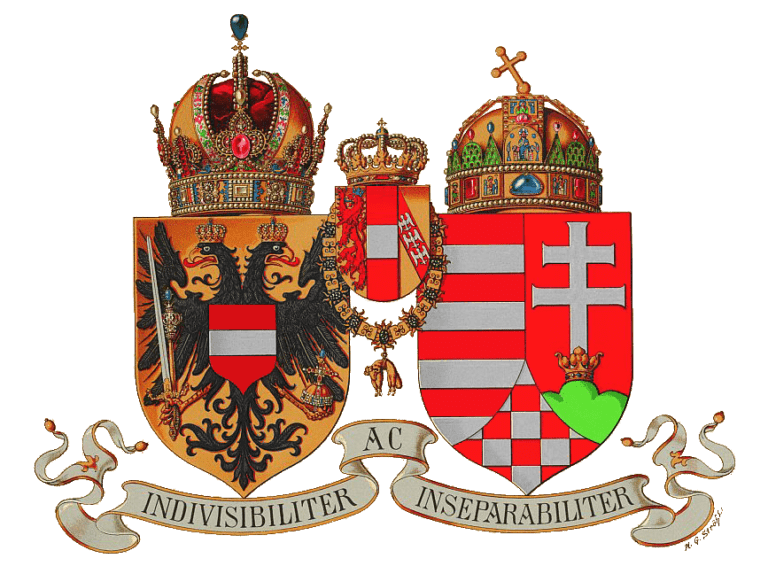

The demise of the Habsburg Empire in 1918 triggered a bitter conflict over the region of German West Hungary between Austria and Hungary. This struggle for sovereignty between the two former imperial brothers threw up several historical anomalies, including the short-lived Republic of Heinzenland.

–

It was 1918 and brand new countries were being born from the ashes of the Habsburg Empire in the aftermath of WWI. Czechoslovakia, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, and of course the new Hungarian and Austrian states as shrivelled remnants at the heart of the once sprawling imperial polity. A new Europe was being born.

Borders were drawn where previously none could have been imagined. Ethnic Germans, Hungarians and Slovenes suddenly found themselves minorities in new countries — separated from their brethren by seemingly arbitrary new lines on the map.

After centuries of being a peaceful, multicultural joining in the great Austro-Hungarian jigsaw puzzle, the agricultural region of German West Hungary (Deutsch-Westungarn) now found itself being claimed by both the fledgling Republic of German-Austria on the one side and the Hungarian People’s Republic on the other.

German West Hungary in the Habsburg Empire

While the Habsburg Empire was still alive, German West Hungary was never a unified administrative region. It was simply a geographical description of an area between Austria and the Kingdom of Hungary which was mainly populated by German-speakers, along with Hungarians and other minorities such as Slovenes and Croats [1].

Even though there was technically a border between Austria and Hungary at this time, it was so “soft” as to not to cause any great tensions among the different ethnic groups as to who belonged where. Although certain nationalist fancies did circulate in the period before WWI, these were academic pursuits confined to a few radicals and did not catch the imagination of the local population.

The kind of virulent social and ethnic tensions which accompanied nationalist movements in other areas of the Habsburg Empire simply did not occur in this little corner of Austria-Hungary. Life went on quietly, peacefully, idyllically.

The conflict which came out of thin air

Therefore, the prolonged territorial struggle which broke out over German West Hungary after 1918 might appear to have sprung from nothing. Some argue that the convulsions of the Great War and the ensuing collapse of the Habsburg Empire combined to create the ideal conditions for fringe and radical ideas to take centre-stage for real-life experimentation. When one reality suddenly evaporates, ideas which were previously unimaginable suddenly become possible and acceptable.

Another theory behind the post-1918 fight for sovereignty over this land tract was of a more practical nature. During the war and its immediate aftermath, Vienna was dependent on German West Hungary for its food supply. Food shortages which had already begun during the war worsened when thousands of refugees poured into the city from the former Habsburg territories as the old empire imploded. With large numbers of people destitute and starving, losing the agricultural resources of German West Hungary to the new Hungarian state would have made the situation untenable. Austria could not back down.

The struggle for sovereignty begins

Even in the final days of the war, it was clear in both Vienna and Budapest that the dual monarchy was on its deathbed. As a wave of revolutionary zeal spread across the former Habsburg territories, the first tendrils of new state action began to make themselves evident.

In Hungary, the Hungarian People’s Republic was proclaimed by the Hungarian National Council under the leadership of Mihályi Károlyi. Through late October and early Nobember 1918, local branches of the Hungarian National Council began to move into German West Hungary, purporting to take over the public administration.

Meanwhile, the new Austrian State Council in Vienna claimed the towns of Ödenburg (Sopron), Eisenburg (Vas), Wieselburg (Moson) and Pressburg (Bratislava) on 12th November.

Following the doctrine of the right of the right to self-determination as promoted by US President Woodrow Wilson, they argued that the new Austrian state should be based on the idea of German speakers coming together to govern themselves in a single political unit. Therefore, German West Hungary, being predominantly German-speaking, should form part of the new Austrian state.

This seems logical enough, but was bound to cause utter confusion when applied on the ground to a local population quite unused to thinking of their lives and co-existence in these legal and theoretical terms.

Competing for hearts and minds

Realising that winning over the hearts and minds of the local population was key to prevailing in the competition for German West Hungary, the government in Vienna set up a network of Western Hungarian Bureau (Westungarische Kanzleien) across the region. These agencies began to spread pro-Austrian, anti-Hungarian propaganda among the locals, preparing the ground for an eventual annexation to Austria.

As the propaganda campaign took effect, pockets of unrest broke out as German-speakers soured on their Hungarian neighbours. In the town of Mattersburg (Nagymarton), civilians protested against Hungarian rule by chasing out Hungarian civil servants and began to acquire weapons in order to take physical control over the town. It was in this febrile atmosphere of nationalist propaganda, power vacuum and ethnic tension that the Republic of Heinzenland would be born.

Heinzenland: the 2-day republic

On the evening of the 5th December [2], Hans Suchard, a local Social Democrat, proclaimed the Republic of Heinzenland [3] in the Hotel Post in the town of Mattersburg. This tiny state would include the German-speaking municipalities in German West Hungary and have Ödenburg (Sopron) as its capital.

Although the circumstances made full annexation to Austria seem impossible, the German-speaking revolutionaries hoped for some kind of economic union with the larger Austrian state and their ethnic kin.

This bizarre action seemed to have been born of frustration from the inability of Austria and Hungary to resolve the conflict — but also of a certain opportunism. Hans Suchard is quoted as saying:

“Bei Ungarn wolln ma net bleiben. Nach Österreich lasst ma uns net. Na, dann ham ma halt a eigene Republik gmacht.”

(“We didn’t want to be part of Hungary. We weren’t allowed to become part of Austria. So we just proclaimed our own republic.”)

An operatic farce

The Heinzenland project was a fiasco. An operatic farce. The revolutionaries, full of “have-a-go-hero” bravado, had failed to properly think through and plan their campaign.

Although their aims garnered a certain sympathy among the German-speaking population of German West Hungary, locals had not been sufficiently informed of the plan. They were therefore unable to properly organise themselves along the lines of typical state structures.

With no real leadership or coordination, Heinzenland was condemned to failure before it even began. Weapons shipments from nearby Wiener Neustadt, which would have helped the citizens of Heinzenland to defend and control their tiny new country, were blocked. It was only a matter of time until it would be attacked and neutralised.

Indeed, during the night of the 6th December, Suchard was arrested by the Hungarian Gendarmerie and sentenced to death, although this sentence would never be executed.

The Austrian government — probably trying to avoid fanning the flames of conflict with Budapest— denied any involvement in the establishment of the Republic Heinzenland. To this day, it remains unclear who the driving forces behind this short-lived sovereign entity were.

The conflict rumbles on

The brief, bizarre episode of Heinzenland did nothing to resolve the larger question of German West Hungary’s fate. The new government in Vienna was unable to enforce its claims to the territory; their counterparts in Budapest seemed to be playing for time while dealing with their own internal instabilities. For their part, the allied war victors showed no interest in getting involved in this particular territorial brawl.

The ongoing uncertainty of this power vacuum opened the door to other, quite fantastical ideas. Indeed, for a brief period, the possibility of German West Hungary becoming a kind of “Slavic corridor” between the newly-formed Czechoslovakia in the north and the Serb-Croat-Slovene Kingdom in the south was discussed, only to be discarded again in short order.

International settlements

The Treaty of Saint Germain, signed on September 10, 1919, was the first step towards a conclusive resolution. Under this treaty, Austria agreed (among other things) to dissolve the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, recognise the successor states and give up its aim of unifying with Germany. In return, the new republic was awarded German West Hungary, including Ödenburg/Sopron.

This was followed on 4th June 1920 with the Treaty of Trianon, which decided the fate of Hungary. This agreement saw Hungary losing 70% of its former territories, including German West Hungary.

Difficult enforcement

Even though international treaties governing the territory of German West Hungary had been signed, practical implementation and enforcement quickly proved to be a thorny issue.

With local political forces on the ground still favouring a return to Hungary and Austria lacking the military capacity to enforce an evacuation of the Hungarians from the territory awarded to them, the conflict rumbled on. Hungary, unhappy with its settlement under the Treaty of Trianon, issued demands for a revision, continuing to claim German West Hungary.

An inter-military commission was established at Sopron to solve the impasse, which led to Hungary agreeing to relinquish its territorial claims to the region. Yet even this diplomatic success would be short-lived: when Austrian gendarmes, civil servants and civilians moved to Sopron in August 1921 to take over the regional administration, they found themselves faced with the so-called “Western Hungarian Uprising”.

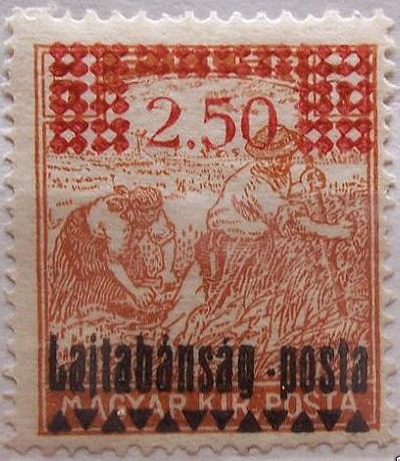

This movement was led by the “Rongyos Gárda” (“Scrubby Guards”), a Hungarian paramilitary unit led by the reactionary Pál Pronáy. This motley crew of volunteers and former anti-Communist fighters conducted guerilla warfare across German West Hungary for several months in summer and autumn 1921. In fact, they managed to clear the area to such an extent that they proclaimed another mini-republic — the “Banate of Leitha” (Lajtabánság) on 4th October. This state had its capital at the Hungarian-speaking town of Oberwart (Felsőőr) and, during its short existence, even managed to issue postage stamps (see below).

–

Italian mediation

In a bid to end the crisis once and for all, Italy stepped in and offered to mediate between the two bickering countries, resulting in the Venice Protocol. According to this settlement, the Hungarians would evacuate German West Hungary and disarm the Scrubby Guards, ready for the territory to be surrendered to Austria according to the Treaty of St. Germain.

In return, the Hungarians were promised a plebiscite on the fate of Ödenburg/Sopron and the surrounding settlements. Austria consented — no doubt betting that the referendum would go its way and it would walk away with the whole of German West Hungary.

In-keeping with the complicated story of German West Hungary, even this plebiscite was delayed: this time by a last-ditch attempt by Emperor Charles I to retake the Hungarian throne from his base in Sopron. The action was quickly defused and Charles was exiled to Madeira with his family where he died shortly afterwards, broken and demoralised.

Under pressure from the Little Entente and with stern warnings from both France and Britain, the Hungarian parliament passed a law to dethrone the Habsburgs and neuter any further risk of them performing similar comeback stunts.

Burgenland is born

Pending the referendum on the fate of Ödenburg/Sopron and the surrounding settlements, German West Hungary was handed over to Austria on 5th December 1921 — the new federal province of Burgenland was to be established on 1 January 1922.

The Austrians had hoped to make the picturesque Ödenburg/Sopron the capital of its new province — but it was not to be. The plebiscite under the Venice Protocol, which was held from 14–16 December 1921, returned a clear result. 65% of voters wanted to remain a part of Hungary.

Any Austrian discontent about the validity or result of the referendum would be irrelevant: this episode in history was now closed. After a brief stint at Bad Sauerbrunn, the provincial capital of Burgenland was moved to Eisenstadt — where it has remained ever since.

In a sign of the lingering hope that Sopron would at some point come back to Austria, no specific town has ever been declared the provincial capital in Burgenland’s constitution [4].

Meanwhile, the Hungarians mourned the loss of this historic tract of territory at their western flank. Only with both countries joining the EU and the Schengen passport-free zone has the sting been withdrawn from this post-imperial wound.

Footnotes:

[1] Ethnic Croats moved to this area during the 16th & 17th centuries, fleeing the Ottoman Empire and attracted by the promise of better lives and opportunities in Habsburg territories. Many villages in this area of the Habsburg Empire had been devastated by the Turkish army and were in need of repopulation. By moving into the deserted settlements in German West Hungary, Croats gained a safe place to live while their presence formed a useful buffer between Austria in Central Europe and the Ottoman Empire in Southeast Europe.

[2] Some sources say 6th December.

[3] The name “Heinzenland” (also written “Heanzenland” or “Hianzenland”) came from the word “Heanzen”, the colloquial name for the German-speaking inhabitants of German West Hungary who emigrated there from Bavaria and other places. The exact origins of the name “Heanzen” remain unclear.

[4] In an ironic historical twist, none of the “Burgs” for which Burgenland was named — Eisenburg, Ödenburg, Wieselburg and Pressburg — are now located in Austria. Eisenburg, Ödenburg and Wieselburg are called Vas, Sopron and Moson and are now located in Hungary. Pressburg is called Bratislava and is the capital of modern-day Slovakia.

—–

Related articles:

The Thayatal National Park – hiking through European history

18 years living in Vienna – some thoughts on a special anniversary

Sopron, Hungary – A daytrip to visit the “wild neighbours”

Vienna’s little treasures – hidden in plain sight (Part I)

—–

Featured photo: public domain