Historic jewels even the locals overlook

—–

I moved to Vienna from Britain in September 2004. Initially, I wasn’t sure how long I was going to stay, so I decided to make the best of whatever time I had in this magnificent city and visited all the main sights in short order.

Schönbrunn Palace, St. Stephan’s cathedral, Belvedere Palace, Karlskirche, Prater…this place is just brimming with wonderful things to see and do! If you’re lucky enough to be here for a longer period, you can get off the beaten path and discover some of the city’s lesser-known gems.

After almost 20 years living in Vienna, it’s these tiny, unknown points of interest that make out the charm of the city I now proudly call home. The ones standing unnoticed on street corners, in shop basements, or even next to train lines. Passed by thousands of people every single day, they are part of the urban furniture and topography…and yet only a few locals know their true significance.

Time for me to let you in on a few of Vienna’s little secrets…

–

Heumühle (“Hay Mill”)

Tucked away in a tiny courtyard in the 4th district, a stone’s throw away from Karlsplatz, the Heumühle (pictured above) is a monument to the area’s past.

The nearby U4 subway line follows the line of the Vienna River (“Wienfluß”), a lively tributary of the Danube that runs down to the river from the surrounding hills. During the 13th century, a mill stream was built to divert water away from the river and power a series of watermills: the Bärenmühle (“Bear Mill”), the Schleifmühle (“Grinding Mill”) and the Heumühle (“Hay Mill”).

Milling in this area continued until the mid-1800s when the mill stream was filled in and both the Bärenmühle and the Schleifmühle were demolished to make way for new urban developments as the city grew. The Bärenmühle is commemorated in the name of a block of modern flats built on the site, as well as the passageway built through a part of it (Bärenmühlhaus, Bärenmühldurchgang). The Schleifmühle lives on in the name of a street in the area – where several of my favourite night-time haunts are located.

Only the Heumühle remained standing. Surrounded by new buildings, the privately-owned building was simply left to crumble for many years.

That solid 14th century construction wasn’t going anywhere too fast though – and a renovation in 2007 returned the mill to its former glory (or at least structural soundness). These days, the mill houses the showroom of an office furniture company and can be viewed by curious members of the public during the day when the gates to the courtyard are open.

Josephinian column (Josefinische Säule)

Being an ancient city with multiple layers of history, there’s plenty to discover under Vienna’s streets – from Roman remains to concealed waterways to cinematically famous sewers (think: The Third Man).

A particularly special feature of subterranean Vienna can be found in the first-level cellar of the house on the corner of Ertlgasse and Kramergasse in the 1st district (now occupied by a shop).

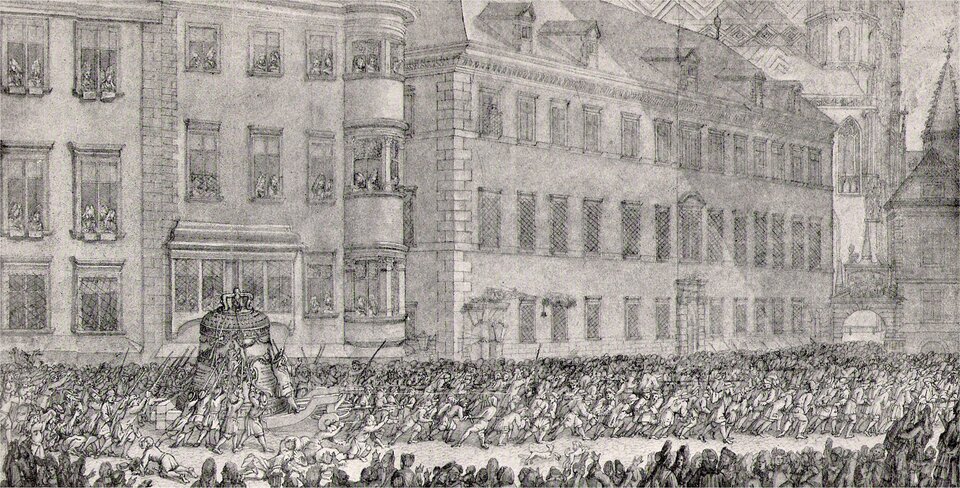

The vaulted ceiling of the old brick cellar contains one of only two surviving “Josephinian columns”. These supports were built into the cellars of the houses lining the Rotenturmstrasse in the early years of the 18th century in preparation for the transport of the famous “Pummerin” bell from the shores of the Danube to its destination, St. Stephan’s cathedral.

The Pummerin bell, partially cast from the iron of Turkish cannons captured during the siege of 1683, was so heavy that people feared transporting it up the street would cause the street to buckle and collapse into the cellars below. Holy Roman Emperor Josef I ordered these columns to be built into the foundations of the surrounding buildings to help this project of city pride to its completion.

The old Pummerin bell hung in the north tower of St. Stephan’s cathedral until 1945 when it suffered a devastating fire in the final months of the 2nd World War. The vast bell fell to the ground, smashing into several pieces. The new Pummerin, in situ since 1957, is only rung on important occasions (e.g. the death of the Pope, new year). Just like its predecessor, it is a beloved symbol of peace and regeneration after the carnage of war.

Maria am Gestade – the “kinky” church

Close to Schwedenplatz lies one of Vienna’s oldest churches: Maria am Gestade. “Gestade” is an old German word meaning “shore” or “bank”. Looking at the church in 2023, this might seem a little confusing as it clearly isn’t located next to the river and the Danube canal is still a few minutes’ walk away. However, before the Danube was regulated in the 16th century, this church did actually sit on the banks of an arm of the mighty river. Local lore tells that this is the place where river fishermen would dock and say their prayers.

Besides being a very beautiful building and marking the start of a pilgrimage route, the church has an unusual feature which harks back to Vienna’s earliest days as a Roman settlement. If you stand at the main entrance of the church and look down towards the high altar, you will see that the building has a slight “kink” in the middle.

This subtle asymmetry in the church’s construction is because it was built along the lines of the early city walls – which themselves followed the boundaries of the Roman camp of Vindobona. Romans, being fans of both symmetry and sound military logic, built their garrison in a rectangular shape with two sides backing onto the river and its direct tributary, the Ottakring stream. That left them with only two sides to defend in the event of an attack. However, being at the intersection of two waterways left them seriously exposed to the risk of flooding.

Which is exactly what happened. Archaeologists believe that extreme flooding in the 4th century resulted in the northernmost corner of the Roman settlement (located at the point where the Ottakring stream flowed into the Danube) collapsing into the river and being swept downstream (check out this illustration for a better understanding).

The pragmatic Romans adjusted to the reformed geography and rebuilt the settlement’s boundaries along the new, post-flood line of the river bank: the line we now see in the crooked construction of Maria am Gestade.

—–

Click here to read part II of “Vienna’s little treasures“!

Related articles:

What does it mean to integrate in a different country?

The strange story of the 2-day Republic of Heinzenland

Austrian German – 10 fantastic words & phrases everyone should know about

—–

Photos: author’s own (Katharine Eyre © 2023)