Historic jewels even the locals overlook

—–

I moved to Vienna from Britain in September 2004. Initially, I wasn’t sure how long I was going to stay, so I decided to make the best of whatever time I had in this beautiful city and visited all the main sights in short order.

Schönbrunn Palace, St. Stephan’s cathedral, Belvedere Palace, Karlskirche, Prater…this place is just brimming with wonderful things to see and do! If you’re lucky enough to be here for a longer period, you can get off the beaten path and discover some of the city’s lesser-known gems.

After almost 20 years in the city, it’s these tiny, unknown points of interest that make out the charm of the city I now proudly call home. The ones standing unnoticed on street corners, or in shop basements, or even next to train lines. Passed by thousands of people every single day, they are part of the urban furniture and topography…and yet only a few locals know their true significance.

It’s time for me to let you into a few of Vienna’s little secrets…

–

The chapel of St. Januarius (Januariuskapelle)

If you follow the Ungargasse from Landstrasse, just before you get to the Rennweg regional rail station, you will pass a large school complex on your left. A striking monstrosity of 1980s architecture with an incongruous centrepiece: a baroque chapel.

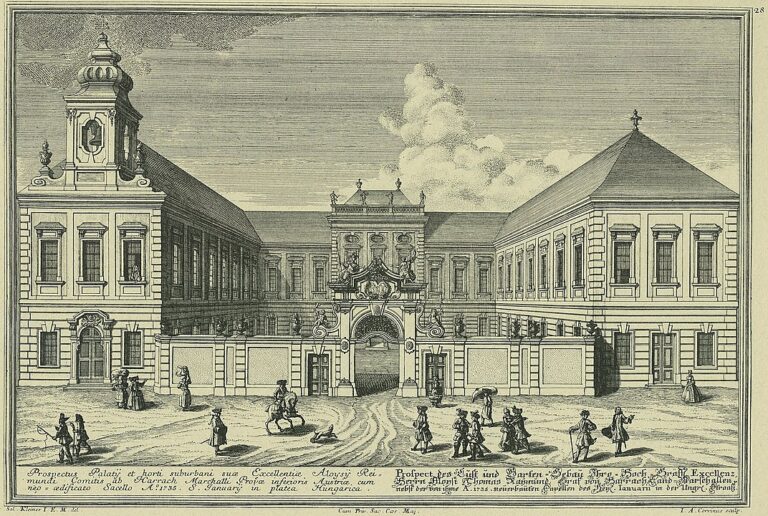

This dinky little building is all that is left of the Harrach Garden Palace (“Gartenpalais”). This once grand building (see title image above) was commissioned by the powerful Austrian politician and diplomat Aloys Thomas Raimund, Count Harrach, in the 1720s. Having acquired an older house on the site as well as several plots of land, he engaged the Baroque architect Johann Lucas von Hildebrandt to build a spectacular garden palace. It was to be a country residence so impressive in its dimensions and style as to provide a worthy counterpart to his existing “town palace” on Freyung.

Over the next 200 years, the Harrach Gartenpalais would go through several incarnations. Passing through the ownership of several Habsburg emperors; its gardens were used as fruit orchards and vineyards to supply the imperial court. Later on, a part of the property was parcelled off for the construction of the nearby Rudolfstiftung hospital. Meanwhile, the building itself was used for a time as a sugar factory, before being turned into military barracks. Tenants included the k. u. k. Militär-Reitlehrer Institut, the authority responsible for training riding teachers for the imperial army. Indeed, a part of the building which used to house the stables remains in the façade of the modern-day hotel opposite the chapel.

The Harrach Gartenpalais met its end in the final months of World War II – destroyed by allied bombs. Its ruins were demolished in the late 60s, leaving only the burnt-out remains of the court chapel behind. This had to wait until 1987 for its own facelift when the adjoining school was built.

It now stands as an inner-city curiosity – its story unknown to the majority of the locals who pass by it every day.

Retzengraben (1st district)

One of the things I love most about Vienna is its topography. Built on the last rolling hills running out from the Alps down to the mighty Danube, the city is full of ups and downs – something which you only fully appreciate when you ride around it on a bike!

While most of Vienna’s hills and dales have natural origins – the lay of the land in some places is a result of human earthworks.

Right in the centre of town, between Naglergasse and Wallnergasse is the rather splendidly-named Haarhof. It is a tiny through-way which opens up into a little courtyard with several pleasant cafés and the famous Esterházykeller restaurant – a firm favourite among the thousands of tourists who come here every year.

As you walk from Naglergasse towards Wallnerstrasse, you will notice how the street drops down. Congratulations: you just left the confines of the Roman garrison of Vindobona and went skidding down into the surrounding ditch! If you had been around a few thousand years ago, that is…

This section of the moat was called “Retzengraben” – probably stemming from “Rattengraben”, meaning “the ditch of rats”. Don’t worry – as you can see from the picture below, there are no vermin in sight these days. It’s all quite genteel!

[For the geeks of the truly committed variety among you: If you stay on Naglergasse and walk towards Freyung, you will see how Naglergasse peels off dramatically to the right before it meets Heidenschuß. The street is again following the boundary lines of the ancient Roman settlement – in this case, you are skirting its westernmost corner (see this illustration for a better idea).]

Old city walls

Over its long life, Vienna has had several sets of city walls. The first were the aforementioned fortifications surrounding the Roman garrison town of Vindobona – followed by the early medieval city wall (“Burgmauer”) that followed more or less the same lines. Then came the “Ringmauer” – covering an area almost three times the size of the original Roman settlement and including vineyards and arable land.

[Fun fact (especially for English readers): the Ringmauer was paid for with the ransom extracted from the English for the release of Richard the Lionheart from his post-crusade captivity in Dürnstein (about 60km west of Vienna). It stood until the 16th/17th century.]

After the Ringmauer came the “Linienwall” which enclosed the area now covered by the 1st through 9th districts. This was completely demolished during the 19th century as Vienna grew and grew in line with its status as the glittering capital of the sprawling Habsburg empire.

Well – almost completely demolished. Fragments of this brick fortification can still be seen at a couple of locations around its former perimeter. One of these is at the Landstrasse Gürtel, close to the Belvedere Palace and the Main Station (Hauptbahnhof). At the edge of the Schweizer Garten park, forming part of the siding of the main regional rail line running through the city, this little piece of city history sits – mostly covered by foliage and graffiti, and mostly unnoticed by the thousands of passengers who whizz by it every single day.

I only realised its significance during the pandemic lockdowns when the restrictions on using public transport meant having to find new running routes around where I live. Crossing over the rail bridge one day, I noticed red bricks just over the bridge railings. What was that? The remains of an old house or earlier bridge? A quick search online let me know that – 200 years ago, I would have run straight through the city walls.

How about that?

—–

Related articles:

Vienna’s little treasures – Part I

Look up! Standing under chandeliers

Austrian German – 10 fantastic words & phrases everyone should know about

What does it mean to integrate in a different country?

—–

Title photo: public domain

Photos of Haarhof and Januariuskapelle: author’s own (Katharine Eyre © 2023)