Isolde Maria Joham: a versatile Austrian artist whose futuristic vision was recognised just in time

—–

The Viennese are known for being a conservative, slightly stuffy lot. They like to turn their noses up at new things. Which is ironic, the city having been home so many creative geniuses over the centuries. You’d think it would be a bit more accommodating.

Take Eduard van der Nüll, one of the architects of the State Opera (Staatsoper) on Vienna’s splendid Ringstrasse. Upon the building’s completion in 1869, the public reaction to it was so negative that Van der Nüll was driven to suicide. Today, the Staatsoper is one of the Austrian capital’s iconic sights, visited by tens of thousands of tourists and opera fans each year. If only van der Nüll could have known.

Similarly, the art of expressionist painter Egon Schiele provoked revulsion among the Viennese public while he was alive. (Although, he didn’t exactly help himself by adopting highly unusual lifestyle and painting prepubescent girls with not many clothes on.) It was only years after Schiele’s death in 1928 that his art became desirable. Today, it is wildly sought after and sells for millions at auction.

Saved from obscurity

Isolde Maria Joham came close to suffering this very Austrian fate, only earning the recognition that she deserved in the final years of her life. In fact, she died on the last day of the first full exhibition of her work in the Landesmuseum Niederösterreich in Krems in October 2022.

With Joham, Austria lost one of its most versatile and exciting artists of the postwar period. But also one of the most obscure. A number of her works are located in prominent public places in and around Vienna and are seen by thousands of citizens every day – but almost no one knows her name.

I first came across her work on a visit to the Don Bosco church in Vienna’s 3rd district as part of an “Open House” event in September 2023. After learning about the church’s ultra-modern concrete architecture and other modern artworks, our guide moved over to the right side of the church and drew back a curtain.

Behind piles of stacked chairs and other churchgoing paraphernalia, came a glow of intense blues and reds, crosses and hearts. This stained-glass window, we were told, was the work of Isolde Maria Joham, a pioneering glass artist of the time (1960s).

I knew her without knowing

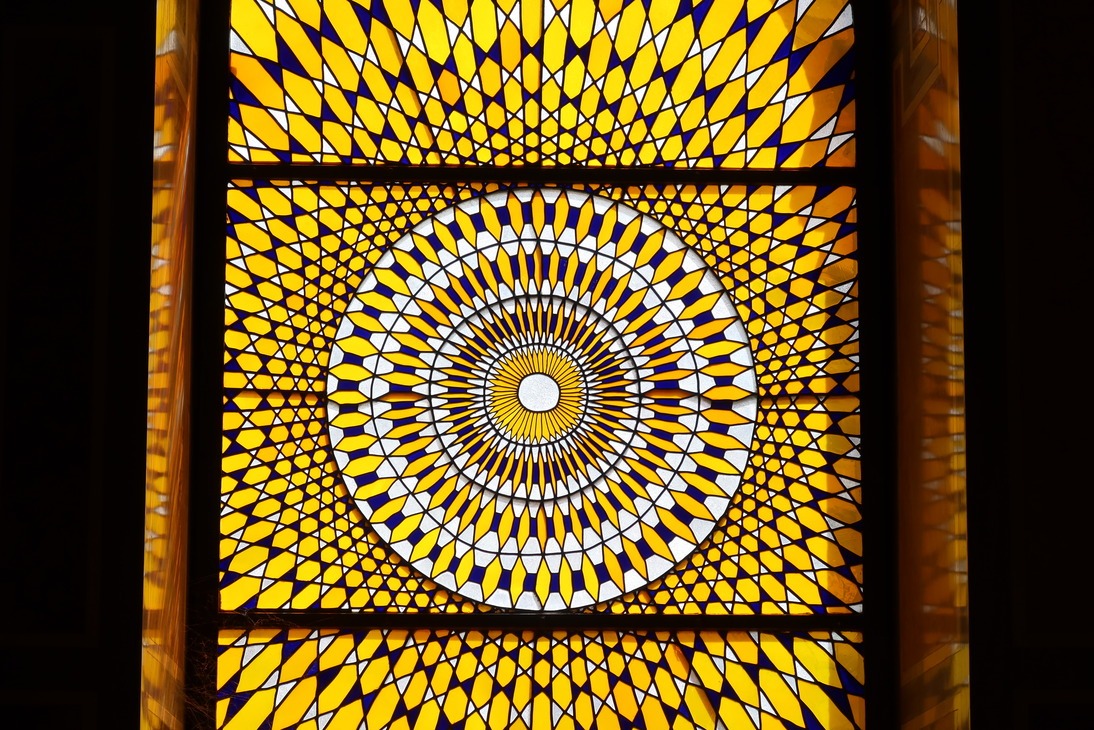

As it turns out, we were already familiar with Joham’s glass work: she was the creator of the dazzling mandala-style stained-glass windows that light up the staircase at the Museum of Applied Arts (MAK).

Besides these psychedelic designs, she also made windows for churches in Lower Austria (Friedhofskapelle Sooß) and Germany (Selb) and the massive mosaic in the waiting room of Vienna’s Lorenz-Böhler Unfallkrankenhaus.

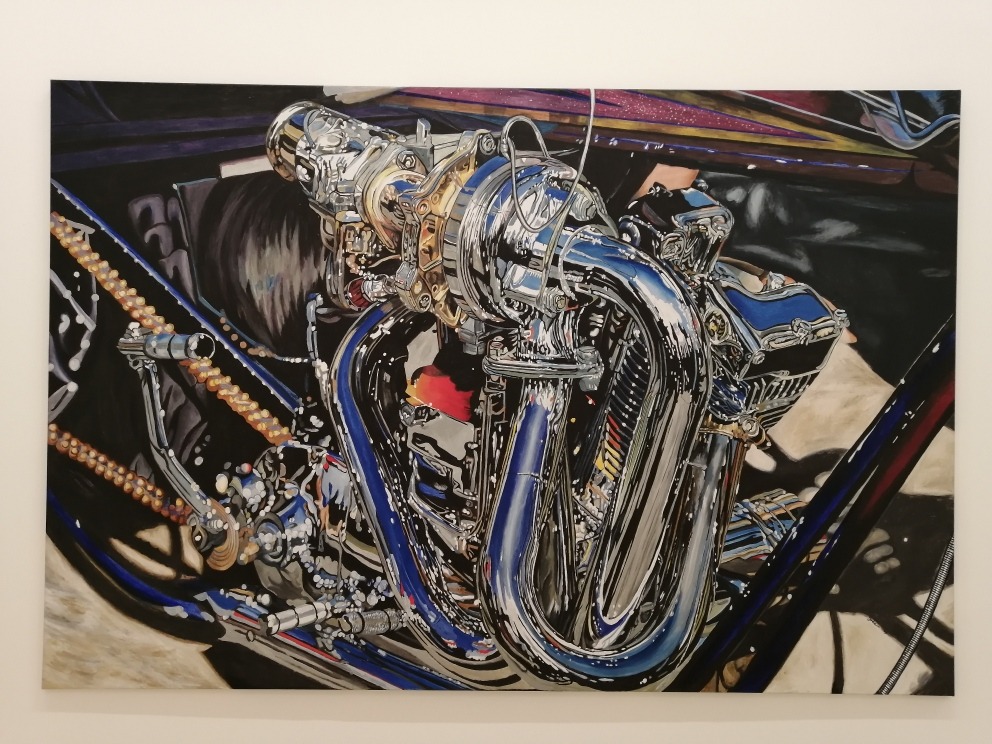

Although Isolda Maria Joham had always painted, this medium only became the main pillar of her work in the 1970s. And she painted BIG. Quite unintimidated by the dimensions of large works after her oversized glass and mosaic projects, Joham now devoted her artistic energies to monumental paintings. Her chosen genre: photo realism.

But with a difference: while other photo-realism artists assiduously reproduced their works from actual photos, Joham eschewed such prompts.

Besides true-to-life images, such as a closeup of the shiny pipes and mechanics of a Harley-Davidson motorbike engine, Joham also dived fearlessly into the realm of fantasy. Her pictures superimpose wild animals and birds on industrial, technological, even dystopian backdrops, highlighting the ambivalent relationship between technology and the natural world.

Melancholy undercurrents

This was the phase in which Electric Rider was created (1981). A cowboy, dressed in a sparkling Stetson and studded shirt stands before the bright lights and commercial attractions of Las Vegas. Far from the ranch landscape of his cultural origins, the cowboy looks melancholy, lonely and downcast; he appears at once fitting and as a foreign object.

Even though we are quite used to seeing the image of a cowboy in a highly commercial setting – as part of a brand, on advertising, fictionalised and romanticised in films – there’s something about this one that leaves the viewer uncomfortable. Is he mourning the loss of his links to work in the natural world, swapped for the superficial attractions of money and public adoration?

Despite the glare of the cheerfully twinkling lights and promise of entertainment and glee, we cannot escape the undeniably melancholy undercurrent and the feeling of something having been irretrievably lost in the stampede towards modernity.

Integrating Asian cartoon culture

Joham’s fascination with modern culture developed through the 1990s and 2000s to cover robots as well as the cartoon and comic figures she saw on her many visits to Korea, Japan and China. Images of animals were replaced by huge robots, Manga and Pokemon figures – perhaps a depiction of society’s inexorable shift into the digital sphere and the rise of robots and AI.

While these huge pictures are dazzling and impressive, Joham clearly had an uncomfortable message for the world. She was using her art to show – perhaps warn – us of the price of technological development. At first for our environment and natural habitats, then for our humanity itself.

A world is coming in which human presence and human work is becoming less and less relevant.

Are we ready?

—–

More from the Great Art Encounters series:

The Ben Shahn murals at the Wilbur J. Cohen Federal Building

Tribute to Chopin by Jerzy Duda-Gracz

The Slav Epic by Alphonse Mucha

Related:

Look up! Standing under chandeliers

—–

Photos: Katharine Eyre © 2024